-

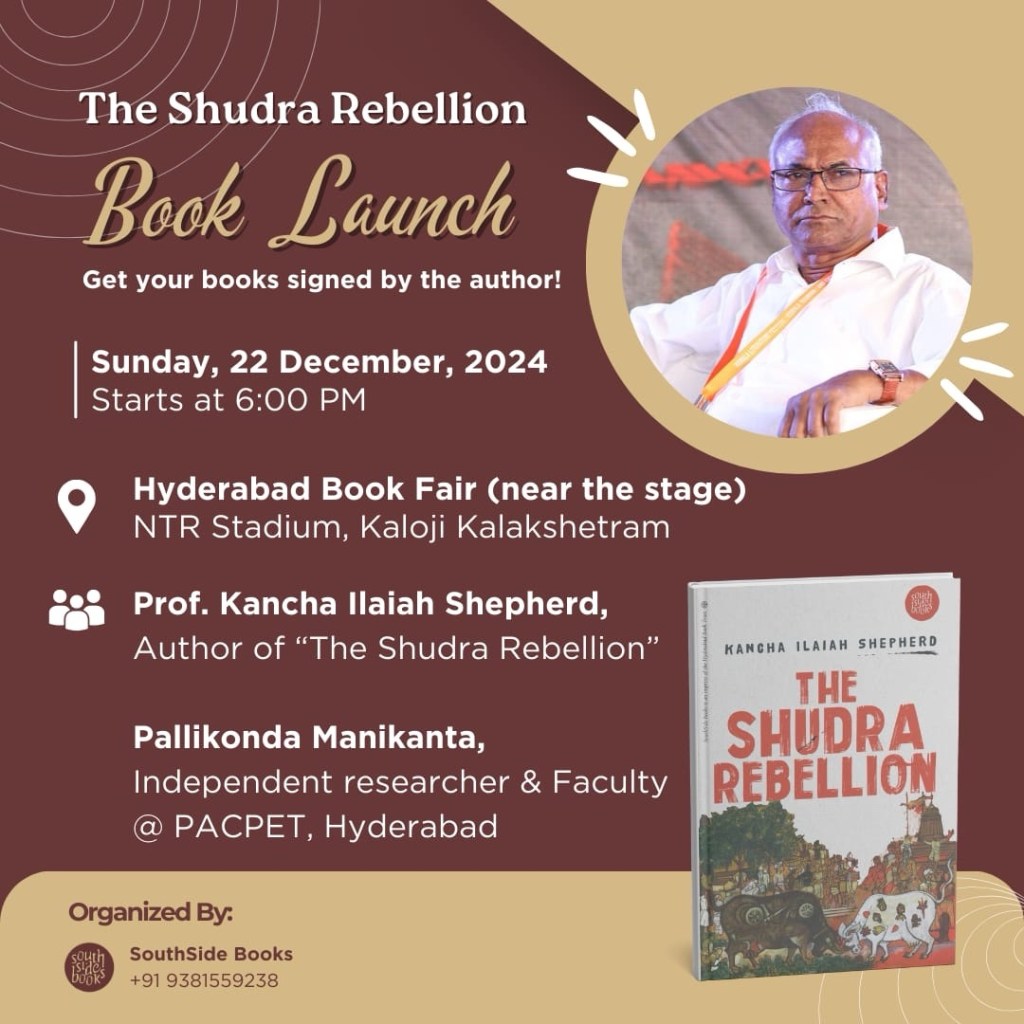

Book Launch – The Shudra Rebellion

-

Kancha Ilaiah brings focus on Shudra castes in his latest The Shudra Rebellion

The author explains how Kancha Ilaiah, in his latest book ‘The Shudra Rebellion’, posits the link with labour of different caste communities as a more credible way of reading caste both in the present and historically.

Written by: Karthik Raja Karuppusamy

Edited by: Maria Teresa Raju

15 Dec 2024

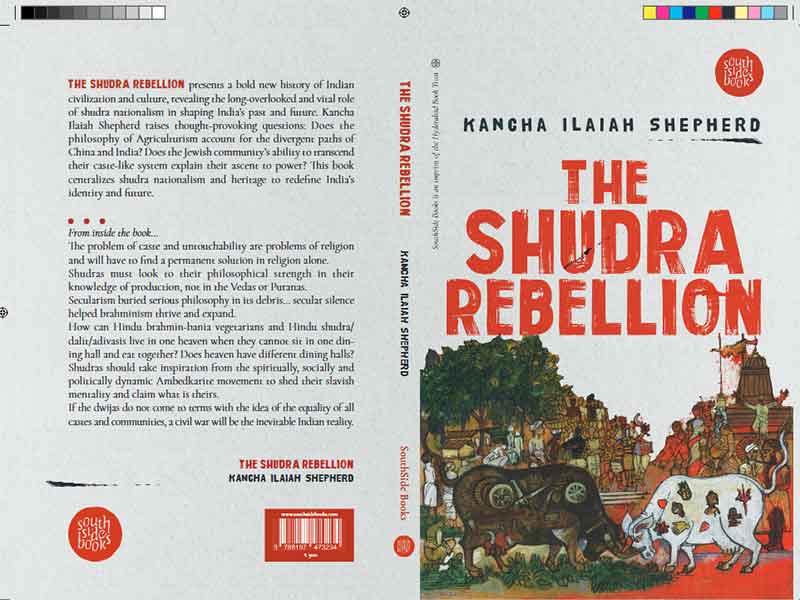

Going against the obvious but misinformed approach of focussing the discourse on caste entirely on either Brahmins or Dalits, Professor Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd brings Shudra castes squarely into the discussion in his recent book The Shudra Rebellion. He reinterprets the historically servile Shudras as the productive communities and civilisational builders.

Often termed an ‘internal matter’, caste inequalities within the rubric of Hinduism are reduced to a non-issue by those who claim spiritual leadership, and by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Historically, caste has been fought on the grounds of religious freedom, social equality, and human dignity, often involving mass struggles by the oppressed community.

Emerging out of that rebellious tradition, Kancha Ilaiah argues that one cannot envision a post-caste world where the Shudra castes are not involved in a historically-informed and politically-sound churning, as they constitute the majority.

In the past two centuries, social activists, political and spiritual leaders from the untouchables, Shudras, Adivasis, and the missionary community have been analysing the caste system from different vantage points. Ambedkar, Phule, and Periyar, have strongly highlighted the economic cost of caste for the oppressed.

In a significant move, Kancha Ilaiah attempts to integrate into the caste discourse the involvement of different castes in the production process that could make or break a civilisation. In The Shudra Rebellion, he posits the link with labour of different caste communities as a more credible way of reading caste both in the present and historically.

The binary between the spade and the book is central here. The spade represents the collective labour that powers the political economy of a given civilisation. Making obvious the contradiction between Harappan civilisation and the later Aryan wave backed by recent findings by Tony Joseph’s Early Indians, Kancha Ilaiah argues that the Harappan civilisation’s base is spade, representing the labour power that is the preserve of the historical communities of Dalits, Shudras, and Adivasis. In contrast, the Aryan culture, which is said to be the last migration into the subcontinent, centres itself around the Brahminical Sanskrit texts and ritualism, which were mythicised. Kancha Ilaiah questions how a civilisation can establish itself or survive if not for the labour of its members or their participation in the production process.

It needs to be noted here that Kancha Ilaiah has often been criticised for painting historical narratives into grand binary oppositions. The scholarly community is quick to dismiss his scholarship, merely because they could trace a line of the counterfactual. But when fundamental civilisational truths are at stake, we need to steer clear of cherry-picking faults, and have to approach the text – or even the author – in a holistic way.

From a structural-historical point of view, the contribution of Dwijas is net negative towards civilisational building — they have a parasitic existence in terms of their relationship with productive classes. As per the hegemonic Sanskrit texts, manual labour and agriculture are seen as ‘polluting’ tasks. This enables the Dwijas’ artificial alienation from organic labour and forms the basis for the economic appropriation and exploitation that powers the grand illusion of Hindu spirituality. In fact, spiritual and social hierarchy is powered and rendered legitimate by the economic appropriation inbuilt in the Varna system.

Spirituality is supposed to lead the society to a higher moral state. Trapped within the ego-centric – caste can be seen as the collective ego of a community – power politics of religious Brahmins, the real victims are the Shudras and Dalits who look up to Brahminism for spiritual progress. The economic and socio-psychological cost that the Dalit-Shudra, and recently Adivasis, pay for investing spiritually in the Aryan culture is debilitating as it offers no spiritual equality. Even to this day, Shudras and Dalits cannot become priests of Brahminical temples, even if they are as qualified as the Brahmin aspirant.

Despite the obvious spiritual inequality, why do masses still identify themselves with the Aryan religious traditions?

To show the deep rootedness of the Shudra slavery, Kancha Ilaiah goes back in history to show that Shudras, even if they were kings, were under the thumb of Brahmins and the literature they have produced. He accuses Shudra kings of “surrender[ing] the written word to the Brahmin”. Educated Shudra rulers such as Shahu Maharaj are seen complaining to the then Governor of Bombay about how deep and widespread the Brahmin monopoly and hegemony were.

A tradition of literary and written records is crucial for a community to evolve its spiritual traditions as it will enable discussions, debate, and continuing presence over centuries, as Kancha Ilaiah has himself noted elsewhere. The unfortunate state of Shudra castes is that, despite owning significant tracts of agricultural lands, they do not possess a written record of the spiritual and productive lives of their ancestors.

The majority of Shudra castes have their own gods such as Mariamman, Ayyannar, Berappa, or Pochamma. However, these communities are not aware of their traditions older than two or three generations, making it quite easy for RSS-BJP to co-opt the Shudras to Aryan religious traditions and use them as fodder in their political ascendance and periodical aggression against Muslims and Christians.

For this to change, Kancha Ilaiah proposes a radical solution — Shudras, Dalits, and Adivasis should embrace English education to empower themselves on a global scale and engage in philosophically significant issues of our times, rather than focus only on material gain or political power.

This work goes beyond the conventional academic framework by engaging with the spiritual, cognitive, and generational aspects of Shudra consciousness. The free spirit and mind of those labelled as Shudras has been tamed into servility and inferiority for several generations. The state of historical Chandalas and Nishadas and the contemporary Dalits and Adivasis is even more inhumane.

While Brahmins and Dalits constitute the extremes of the hierarchical Aryan spiritual imagination, it was Shudras who were the servile castes who were forced to serve the so-called twice-born Varnas. But how the servile caste, even after having gained relative material progress, still lacks the spiritual and philosophical imagination to break free of the Brahminical worldview is a moot question.

It’s also puzzling why the historical oppression meted out to Shudras did not convince them to accept contemporary Dalit communities as their brothers and sisters in their spiritual and material quest for freedom, equality, and dignity.

For sure, The Shudra Rebellion has the potential to raise more questions than it could answer. As the system of graded inequality is sophisticated, seamlessly subtle and violent at times, the best minds have to face these questions and guide us to an egalitarian future. A communion of the spade with the book – labour with philosophy – is a worthwhile experiment that could enable society to tolerate, if not enable and embrace a human consciousness that is just, kind, and free.

Karthik Raja Karuppusamy is an academic and author, primarily recognised for his work in political studies and social justice. One of his most notable contributions is as co-editor of the book The Shudras: Vision for a New Path alongside Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd. He pursued PhD at the Centre for Political Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, where he explored the role of caste in the political formations at the national, state, and sub-regional level of Kongunad.

-

Why shudras must build museums of agrarian and artisinal instruments

Living shudras are a huge repository of their history.

A creative illustration of the Indus Valley Civilisation. |Tejavalli reddy(1830787), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Shudra history survives and exists in the furrows of agrarian lands and in artisanal fossils and living tools. The living shudras are also a huge repository of their history. India’s science exists in these unwritten furrows and in the deep wells of the wealth of labour. This nation’s future has to be built, taking lessons from these sources.

The day-to-day discourses of shudra food producers are replete with philosophical, economic and scientific thought. Unfortunately, this thought has not been recorded and textualised. Since most of their socio-economic and spiritual history is in the villages, young intellectuals of good calibre must engage in textualising it.

Before you scroll further…

Get the best of Scroll directly in your inbox for free.Shudra civilisation is spread out across many regions and states and is recorded in some regional languages and oral histories. Several scholars must undertake the painstaking work to study and write about shudra philosophy, science, and economics, in all regions and states mainly in English. Though it is not an easy task, given the denial of their history for millennia, it is possible to retrieve it.

There is a major task at hand for shudra voters, activists, leaders and rulers, whether at the state or central levels, to establish good museums of artifacts of production, social use, cultural use and architectural value that survived the historical neglect of the brahminic negative knowledge system. Indian agriculturist and artisanal forces constructed highly sophisticated tools such as spades, buckets, pots, plough, ropes, construction materials like bricks, cots, hunting and fishing instruments as time, production, and survival demanded.

By the time the shudras built the Harappan civilisation, they constructed houses with burnt bricks and built their homes with crafted wood. At the time, the migrant Aryans had no knowledge of such civilisational technologies. Tools and technology development occurred much before the Aryans arrived and constructed the ideology of brahminism. They did not help in the scientific process of life.

Millions of instruments went into oblivion without getting written about or their shapes and uses sketched.Artifacts at the Mohenjo Daro museum. Credit: Saqib Qayyum, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pre-Independence times stored brahminic music or written material in museums, libraries and temples. Kings, whether shudra or dwija, gave importance only to divine idols and sculpture. Even the erotic life of brahminic society was preserved in the Khajuraho and Konark temples, but no king built an agrarian artisanal museum. No ruler had a contemporary sculpted plough placed in a temple. This only shows that agriculture, which is the mother of all cultures, had no value in any mode of civilisational history under pre-colonial, colonial or postcolonial rulers. So far, shudra rulers have not shown any concern for agrarian artefacts or understood the need to museumise them.

ADVERTISEMENT

As a result, this ancient civilisation did not preserve the fundamental source of its culture, science, technology and history. Anti-science brahminism made us slaves of the Euro-American knowledge systems. Hence India borrows science and social science knowledge from them even in postcolonial times.

The shudras must now strive to build many museums of agrarian and artisanal instruments, and write about their modes of use. For example, there is repeated mention of soma (in modern times, this drink is known as toddy, called kallu in Telugu) even in brahminic books like the Vedas. But nobody wrote about what kind of technology was used to tap the drink from trees. Toddy tappers use moku, mutthadu and guji to climb a tall toddy tree, even in modern times to harness the drink.

In ancient times too, the tappers of soma must have used several instruments and techniques, but there is no record of these technological instruments.An illustration of the Pasi community of toddy tappers. Credit: CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

A toddy (sura) tapper has to climb a tall tree that has no branches to tap the drink at the top and bring it down. Using these instruments and risking their lives, tappers do this hard labour with great scientific skill. Every day, the tapper climbs several trees and brings down the drink from the top of the trees. They use the moku to support their back, placing this around the tree stem, while their hands are pressed to the tree. The guji keeps the feet pressed to the tree. The mutthadu holds all kinds of sharp knives that are used to cut the trunk to get the drink from the tree.

ADVERTISEMENT

Likewise, several shudra occupational groups use different technological instruments to perform their skilful tasks. Many such technologies are going out of existence and their history erased if they are not written about. Museums of such tools will be great historical resources of knowledge to remain for millennia.

This op-ed has been adapted from Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s The Shudra Rebellion (Southside Books).

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a former Director of the Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at Maulana Azad National Urdu University in Hyderabad.

-

Philosophy of Agriculturalism in Ancient India

When I was researching for my latest book The Shudra Rebellion I went back into ancient Indian literature to find out whether there was a philosophical school called Agriculturism around pre-Vedic and Vedic period. I did not find any written evidence about this school. I looked at the possibility of such schools existing in ancient China, Greece, Israel and Egypt. We all know that apart from India these countries are the main builders of ancient schools of thought. I found that there was a very powerful school of Agriculturism in ancient China. It thrived between 770 and 221 BCE in China. The main philosopher who propagated and wrote about agriculturism was Xu Xing (372-2389BCE). It remained part of Chinese history.

In fact the Indian agricultural civilizational history was pre-Chinese civilization. When Indian pre-Aryans built the Harappan civilization India had very developed agrarian production whereas China did not have such an advanced agricultural civilization. China’s earliest city was Changzhou, established around 2600 BC, located in the Hunan province. Harappan civilization was much older than this and the Chinese city was much smaller without any evidence of availability of burnt brick, advanced wood craft, bronze tools and so on.

Harappan civilization had shown more mature brain work than any other ancient city civilizational work. Without a properly developed philosophy of agriculturism making advanced scientific tools is not possible. Philosophy and science are closely interrelated mental developmental processes. In pre-Vedic period India had that combined thinking process.

AGRICULTURISM AND VEDAS

After the Vedas were composed and written into texts slowly agriculturalism as philosophy was regarded as unworthy to study and write about. Quite sadly that school slowly went out of existence. That resulted in a massive stagnation of agrarian and artisanal science and production in ancient and medieval India. The fact that leather technology was treated as untouchable, along with its producers, spade and plough were never seen as symbols of civilization of India had weakened the advancement of production. That situation was waiting for somebody to come in.

The Muslim rulers came with a different philosophy, but quickly were surrounded by the Brahminic punditry that told them that in their parampara caste was divine and educating the Shudra/Dalit/Adivasis was out of God’s direction.

In other words the Indian Agriculturism was much more advanced than that of China. That was the foundational philosophy of our nationalism not Vedism. Because caste culture did not allow to write about it and preserve it died. That was because the Pre-Aryan Harappans did not have developed a script and post Vedic agriculturists were declared fourth Varna as Shudra slaves, in which all Shudra caste like present Reddys, Kammas, Kapus, Marathas, Patels Jats Mudaliyars to Chakalis (Washing communities )and Mangalis (barbers) were a part. Hence they were not allowed to read and write till the British opened schools for all of them.

Even the Muslim kings like Akbar went by Brahmin pandits’ advice to keep them away from Persian education.

Even now we see the impact of that historical illiteracy on the Shudra/Dalit/Adivasi masses.

The Shudra Rebellion book examines these hurdles for even financially sound Shudra/Dalit/Adivasis not getting engaged with philosophy even now. The contemporary Dwijas mostly directed by the RSS school do not engage with agrarian philosophy. They keep on telling that Vedas are the source of Indian philosophy. But in those books there is no agrarian knowledge. Nowhere in the world book is seen as a source of philosophy. Books are only a reflection of the people’s philosophy working in the fields. And the Vedas did not reflect that productive field philosophy of agriculturalism.

The Dwija thinkers do not think that Shudras/Dalits/Adivasis are capable of producing philosophical ideas even now. They built a wall between philosophy of agriculturalism and Vedism. This wall of Brahminism destroyed creativity in agrarian production; it did not allow industrial production to grow as it did in China and Europe in present times.

Is it not a fact that in village agrarian communities there are many philosophical visions about good production, land and seed relation, the nature of soil and its relationship to seeds, animals and humans. Do philosophical ideas still play a critical role in our villages or not? Yes they play. Only a generalized philosophical vision around plant, grain, fruit, earth and water of Indians produced food from fields when hunting and fishing was not feeding them enough in a given area. Even now that continuum is there.

The study of agriculturalism as philosophy now is important because the RSS/BJP intellectuals, who mostly came from non-agrarian dwija families, want the Indian children and youth to study only Vedism and mythology in schools, colleges and universities. But there is no discourse around agrarian and artisanal production in these books. The social category that is involved in production, innovation of agriculture and artisan science almost does not exist in those books. Without food producers and artisan skilled workers how did the Vedic and Puranic society exist?

ALTERNATIVE METHOD

The only alternative left to me was a careful study of the present village level agrarian masses to reconstruct the Indian philosophy of agriculturism and trace its roots back to Harappan agriculturism.

In the book mentioned above there is a chapter, Shudra Agriculturalism and Indian Civilization. This is indeed a preliminary study of our philosophy of Agriculturism in comparison with that of Chinese. It defines how agriculture operations in India have philosophical ideas linking with materialism. The Hindutva view is that only religion is linked to philosophy. In fact agriculturism is deeply embedded with spiritual philosophy much before Rigveda was composed and Ramayana and Mahabharatam were written.

By suppressing the agriculturists as Shudra slaves the Vedists also suppressed agriculturist philosophy and that anti-agriculturist philosophical bent of mind continued.

However, a lot of new studies need to be done on Indian agriculturalism. It needs to be given higher status than Vedism, Vedanta, Dwita and Adwaita because agriculturism is the life blood of human survival. Once religion as a philosophical school emerged independent of the philosophy of production and the religious philosophers dominated the knowledge system. However, we need to rediscover great schools like agriculturism and promote them in order to survive as a creative nation. Once upon a time organised religions like the ones we see now were not there and they may not be there after several centuries later.Name: Email:

The philosophy of production and distribution will be part of human life as long as human life exists on this earth. After coming to power in 2014 the RSS/BJP pundits are talking about the parampara of Vedism and want to hand over agriculture to a few monopoly Dwija industrialists, who see it only as a source of profit. The great rebellion of farmers against three farm laws in 2021-22 saved the nation from that danger. My book, the Shudra Rebellion, took birth in this background.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist, author. His latest book is The Shudra Rebellion

-

How a Caste Census Can Lead Us Towards a Casteless India

Reservation is not the cause of caste – it is a consequence. Without dismantling caste-based discrimination, even reservations cannot create a level playing field.

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

In an earlier article, I discussed how Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s slogan, “Ek Rahenge To Safe Rahenge (If we remain one, we will be safe)”, is intended to oppose the idea of a caste census, which Rahul Gandhi has been championing as a key opposition leader. For the first time, a leader from the lineage of Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and Rajiv Gandhi – leaders who historically resisted caste-based reservations and the enumeration of caste data – has taken a firm stand on the caste question. Rahul Gandhi now speaks like an Ambedkarite, frequently invoking the names of B.R. Ambedkar, Jyotirao Phule and Periyar in his public speeches. He has made the demand for a caste census an unavoidable challenge for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-Bharatiya Janata Party government.

Gandhi likens the caste system in India to the hidden iceberg that sank the Titanic in the early 20th century. Just as the iceberg, concealed beneath the ocean’s surface, destroyed the massive ship, the caste system, embedded in the social hierarchies of Indian society, has undermined India’s potential as a nation. Previous governments failed to recognise this “hidden iceberg” and its destructive impact on the fabric of Indian society.

Gandhi is the first major leader from the Congress Party to acknowledge and confront this systemic problem.

Prime Minister Modi, himself from an Other Backward Castes (OBC) community, uses his caste identity to mobilise Shudra OBC votes. However, he claims that a caste census will divide Hindu society – a belief echoed by the RSS and some ‘upper’ caste intellectuals. These groups often avoid naming specific castes like Brahmin, Bania, Kayastha, Khatri or Kshatriya, preferring the vague term “Hindus” to describe their social bloc. This avoidance masks the deep inequalities and hierarchies within the so-called Hindu community.

The term “Hindu” has become a mystical label, often used to obscure the historical exploitation of Dalits, Shudras and Adivasis by ‘upper’ castes. However, the caste census has the potential to reveal the realities of caste-based inequalities and foster unity, not division.

A caste census will identify individuals by their traditional social groups, often tied to specific occupations, and provide an accurate count of their population. While critics argue that this will entrench caste identities, the reality is that caste-based discrimination already exists. A census will simply expose its extent. Crucially, the data will also show how many people have moved beyond their traditional caste occupations, illustrating social and occupational mobility.

For instance, Brahmins are traditionally associated with priesthood, a profession deemed ‘pure’, while Chamars are linked to leatherwork, considered ‘impure’. These labels have perpetuated untouchability and discrimination for centuries. Occupational change is therefore essential for reducing caste-based inequalities. If the census reveals that Chamars are entering professions like teaching or administration, or that Brahmins are engaging in leatherwork, it will indicate progress toward a casteless society.

The ultimate goal is to eliminate caste-based discrimination and inequality. To achieve this, caste names must carry equal respect, and inter-caste occupational mobility must become the norm. Schools, colleges and universities should promote the dignity of all professions and encourage occupational diversity.

A truly casteless society evolves when individuals shift into new occupations, acquire new skills and engage in inter-caste marriages. Inter-caste marriages foster cultural exchange and reduce the rigid boundaries imposed by caste. Caste, after all, has also created significant divides in food habits, rituals and social practices.

B.R. Ambedkar proposed the idea of ‘Annihilation of Caste’, but few substantial theoretical frameworks have emerged since. The intellectual elite, predominantly Dwija (upper-caste), have largely ignored the issue, treating caste as if it does not exist. Even during the Mandal movement of the 1990s, discussions were limited to the merits and demerits of reservation, rather than addressing caste as a systemic problem.

Reservation is not the cause of caste – it is a consequence. Addressing the root issue requires a deeper approach, akin to diagnosing and treating a cancer. Without dismantling caste-based discrimination, even reservations cannot create a level playing field.

Communists, meanwhile, focused on class over caste, leading to their political decline. In contrast, the RSS and BJP have used caste-based representation as a tool for electoral success. However, the RSS’s vision of Sanatana Dharma inherently upholds caste hierarchies and rejects spiritual democracy, preventing any real progress toward equality.

Historically, the Congress failed to recognise caste as a structural issue, leaving space for the RSS-BJP to rise to power. Rahul Gandhi’s ‘X-ray’ analogy – calling for a caste census as a diagnostic tool – is a step toward addressing caste inequalities. A caste census would act as an X-ray of Indian society, followed by deeper analysis (a ‘scan’) and intervention (a ‘biopsy’).

The census would provide comprehensive socioeconomic data, highlighting areas of inequality. While caste identities may persist for some time, the immediate focus should be on eradicating caste-based discrimination and occupational stigma. For example, the belief that a Brahmin’s child should not engage in leatherwork or that a Dalit cannot become a temple priest must be challenged.

Accurate caste data would have other benefits as well. Castes with inflated perceptions of their population may face a reality check, while underrepresented groups may mobilise for a fair share of resources and opportunities. Education, a critical driver of occupational change and inter-caste marriages, would gain renewed focus.

The caste census is not merely a tool for identifying inequalities but a roadmap for building a more equitable society. By understanding and addressing caste-based disparities, India can move closer to Ambedkar’s vision of a society where dignity, equality and opportunity transcend caste.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist, and author. His latest book is The Shudra Rebellion.

https://thewire.in/caste/how-a-caste-census-can-lead-us-towards-a-casteless-india

-

V T Rajshekar: A Shetty Converted To Dalitism Left A Legacy That India Never Knew Before

V T Rajshekar’s death, on 20 November, 2024, though at the age of 93, saddens me deeply in one sense, but allows me to celebrate his life and legacy. He was a friend and a guide of courage and confidence for activists and writers like me across India and beyond. Because of him my book Why I am Not a Hindu got the London Institute of South Asia (LISA) award in 2008. He personally attended the award ceremony in the Westminster House of Parliament (British Parliament) followed by my lecture. We spent a very good time in London discussing world politics and eating together.

He wrote a fine review and made that book popular among his Dalit Voice readers even before I knew him and his journal. He was a man who can open up an immediate quarrel on issues of disagreement, but at the same time reconcile to friendship when topics shifted to agreeable areas. His unwavering stand on Dalit liberation, having come from a Kannada Shetty community, which is also known as Bunt, with a solid journalistic background, with a work experience in The Indian Express is truly remarkable. He remained with Dalitist commitment till his death. No upper Shudra intellectual, leave alone of his generation, even now emerged as such an anti-untouchability and pro-Dalit liberation campaigner.

He said that after he left The Indian Express and started “The Dalit Voice” he lost all his middle class upper caste friends. He managed the writing, printing and distribution of that journal single handedly from his own house in Bangalore.

He turned to Dalitism much before the Mandal silent revolution began. At that time there was no Post-Ambedkar Dalit English reading and writing scholarship. The word Dalit was just becoming noticed only in some media circles because of Dalit Panther Marathi literary movement. Maybe because he was also in Bombay city as a reporter, he immediately understood the importance of popularizing that word ‘Dalit’ by starting a journal itself. But for a Kannada upper Shudra Shetty to take that decision and face the social isolation, particularly in his journalist circles, must have been a torturous course.

Imagine in a Pre-Mandal situation to start an English journal with that title leaving a lucrative journalist job was something unique. As recently as 2024 when Rahul Gandhi asked how many journalists are from Dalit/OBC/Adivasis, in that conference nobody raised a hand. In a national press conference, that too by a major opposition political leader, in the presence of foreign media, this was the situation. VTR must have been the lone Shudra in English journalist Brahminic world to break that cordon of casteism in popular media of the nation. He left Indian Express with frustration because of the casteism in the mainstream media, as he told me, to start a radical Dalit journal to fight his opponents.

He never compromised with the upper caste journalism of India. His articles never appeared in any national English newspaper after he started The Dalit Voice. Whenever there was a discussion about the Indian media he immediately became abusive of its casteism. He used to say that all upper caste Indian newspapers are “Toilet Papers’. When he found out I was writing in national newspapers he would tell me “do not sell your ideas to upper caste people, they do not change”. Of course I would smile and leave it there, as I believed in engaging and writing as much as possible in the mainstream media. Till his death our friendship continued with warmth, in spite of such differences.

His idea of Dalit-Muslim unity was more cemented one than the idea of Dalit-OBC unity. He would say OBCs would go with RSS/BJP more than Dalits do. Though he did not become Muslim himself, was a strong supporter of Islam as a religion.

His trips to Pakistan caused his passport impounding for quite some time. He was a strong anti-Zionist. Repeatedly wrote articles against Jews.

His silence became louder after he shifted from Benguluru to Mangalore because of health reasons in the last days of his life. However, he kept traveling till into his late 80s. The last time I met him was when he came to attend the protest meeting against the institutional killing of Rohit Vemula in Hyderabad Central University in 2016. Unfortunately he was not allowed to enter the campus. Yet he stood protesting for a long time at the gate. That was his commitment to Dalit cause.

A man who always wore khadi kurta and pyjama, would look like a typical Kannada Congress politician. But he was a real converted Dalit intellectual.Name: Email:

Early this year Paul Diwakar and a team digitalized Dalit Voice and they asked me to be there at the Bengaluru Indian Social Institute while the website was being inaugurated, but unfortunately I could not go. However that happened when this legendary Dalit was alive.

It is not possible to think another Rajshekar would emerge who could convert like him from a Shudra upper caste to Dalitism and fight all his life for their liberation. His Dalit Voice was known all over the world—particularly in Africa and in several Muslim countries.

Since he left this land after such a long life, having lived for the cause of liberation of the most oppressed in the world, we need to celebrate VTR’s life, ideas and writings as long as we are also alive. Good by VTR.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist and author.

-

‘The Shudra Rebellion’: Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd studies the vital role of oppressed castes in India

The author examines Shudra nationalism and heritage to redefine India’s identity and future.

Author Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd. | Wikimedia Commons

The slogan-shouting and muscle flexing on the basis of caste and class were in full bloom during the elections in Maharashtra. It is a spectacle for all of India now. These elections have also opened up a Pandora’s box amid the demand for reservation of Marathas (Kshatriyas or Shudras) in Maharashtra. It is the same Maharashtra that had foregrounded the first non-brahmin movement led by Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, along with his partner Savitribai Phule. It was the first act of an assigned Shudrarebelling against the brahmanical patriarchal dogmatic order. Amidst this chaos, I came across a very important and apt intellectual work, The Shudra Rebellion by scholar Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, to understand these times. ughts.

Shudras in the age of frenzy

The book lays out the territory for the reader in terms of time and space, to understand the banal narrative of Hindi, Hindu, and Hindutva. This narrative has inverted the idea of a nation. Nation, the author says, has now been imagined via a cultural communitarian idea. This culture is an extension of the above majoritarian trio crafted by a deliberate and mythical construct of history. This mythologisation of history is the outcome of textuality – a limited birth but worth deciding on systemic structure.

Before you scroll further…

Get the best of Scroll directly in your inbox for free.Subscribe

The author draws attention to the discourse that demeans the bodily labour performed by Shudras, as their work is labelled as polluting. Whereas the work done by Brahmins is upheld as meritorious as well as pure. The beauty of this text is that the author never shies away from mentioning names, and states clearly that this is the typical behaviour of a cultural factory named RSS. In this age of frenzy, Kancha Ilaiah theorises about the category of Shudra and talks about their view of history. In fact, it is like a neo-renaissance for readers. Enumerating several varieties of Shudras – part of the varna system as well as of gender discrimination – who are bereft of dignity, he writes about their lives.

The author foregrounds an alternative history by making the readers rethink the materialistic, philosophical basis and discursive treatment of the Harappan Civilisation in Indian academia guarded by ‘Dwija’ intellectuals. He analyses the mythology, proposes new theories, and uses recent scientific works like that of award-winning Tony Joseph to support his argument of Shudras being the true founders of the civilisation of India, arguing that they lost out to the cunning and manipulation of the brahmanical agents who deliberately demeaned the Spade civilisation of Shudras.

The author’s re-categorisation leads, therefore, to a retelling of the story of two civilisations. He proposes that history-writing has neglected the story of the Spade civilisation, which upheld the dignity of common people, women and their history of labour. But it lost the clash of civilisations and victory fell into the hands of those with bookish knowledge. The author contends that this arrested the civilisational mobility of India when compared with other world civilisations.

This, says Kancha Ilaiah, was also replicated in the world of cognition, and the Shudras were denied philosophical and spiritual democracy. He conducts a comparative study of theories and praxis of different civilisations to make his point, going further out on a limb and comparing it to intellectual black magic, something that took control of the minds of Shudras and women, reducing them to a mere animal-like existence. I couldn’t help but recall our Mahatma Jyotirao Phule’s famous dictum,

Without education wisdom was lost;

Without wisdom moral was lost;

Without moral development was lost;

Without development wealth was lost;

Without wealth Shudras were ruined;

So much has happened through lack of education.One can’t resist comparing the systemic injustice presented here to Hannah Arendt’s work, where she categorises people suffering similarly as being reduced to Animal Laboron.

ADVERTISEMENT

I truly enjoyed reading the chapter on Shudra kings, especially the way the author portrays Shivaji Maharaj and his saga of coronation. Also worth reading is a letter reproduced by Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj, the king of the former princely state of Kolhapur. He is the same maharaja who introduced reservation for backward classes in his administration, and also supported BR Ambedkar’s pending education. He was the first to declare that Ambedkar was to be the future leader of Dalits in the historic Mangaon Parishad, and sponsored Ambedkar’s first periodical Mooknayak. His pragmatic, intellectual analysis of brahmanical societal moralities and attempts to strike strategic alliances with the British to overthrow the brahmanical system is brilliantly put forth by the author. This is an astonishing discovery for readers.

Jyotirao Phule repeatedly visits the text as Kancha Ilaiah analyses his writings, Cultivator’s Whipcord, and Slavery. The author argues that Phule is the true theoretician of the praxis of Shudra labour, and an apt counter to brahmanical textuality. He nudges the readers towards an alternative reading of history, in which they use their own reasoning instead of pre-existing frameworks or “isms”.

The hegemony of culture and language

Using a contemporary cultural and political framework, the author analyses the ideas of English education, local language education, and the idea of the imposition of Hindi. He links it symbiotically to the cultural hegemony of Sanskrit that followed the same methodology earlier. Thus, the book shows that language with its own culture and politics has a huge effect on the crafting of the public sphere as well as on constructing the edifice of self-rule. Kancha Ilaiah doesn’t preach – he suggests ways to tackle these crises. We may agree or disagree with him, a freedom that is of prime and utmost importance in the realm of Constitutional morality.

This work is also to be appreciated for its stand on the 2020 farmer’s agitation movement in India. I was swept away by the fact that a response to a social and political crisis can be a cultural and intellectual one.

VERTISEMENT

Certainly there are lacunae in the text, but the bold ideas presented here compel the reader to ponder over and analyse historical events, the politics of knowledge production, the methodology of deeming some things as pure or impure, and how intellectual hegemony is established. Kancha Ilaiah presents numerous questions that merit several rounds of reading.

The Shudra Rebellion, Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, South Side Books/Hyderabad Book Trust.

-

शूद्र बने ‘पुरोहित’, ताकि भगवान को बता सकें ब्राह्मण-बनिया ने हमपर जुल्म किया- Kancha Ilaiah

-

BJP’s unity-safety call is linked to its aversion to caste census

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses a public meeting ahead of the Maharashtra Assembly polls, in Pune. File photo: PTI Modi govt doesn’t want to collect caste data in next national census; hence it has started a campaign saying a caste census will divide Indian society

On November 11, while campaigning in Maharashtra, Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave a strange slogan ‘Ek rahenge toh safe rahenge! (We will be safe if we are united).

First, let us look at the language in the slogan, which Modi made the entire attendees repeat several times at a public meeting. ‘Ek’ is a Hindi word for unity. Safe is an English word, whose meaning we know.

The language question

Why was he using ‘safe’ in Maharashtra?

Obviously because of the spread of English language in rural areas in that state. If it

were to be Uttar Pradesh, he would not have used an English word in a slogan, that too in public meetings.

Also read | Quota-within-quota is more dangerous form of ‘creamy layer’ concept

He and his party oppose English language getting introduced in government schools.

However, they remain silent when top corporate schools, run by Hindutva supporters, do their high-end business by selling English language to the rich.

But the very same Prime Minister uses an English word in a slogan in a deep rural public meeting because it has to be understood by the people.

The real objective

Let us look at the aim of the slogan.

Earlier, a similar slogan was given by Yogi Adityanath – Batenge toh katenge! This slogan was approved by the RSS. Now Modi uses it with mixed language.

The media has interpreted Modi’s slogan as communal as it is perceived to be against Muslims. But this slogan is aimed at opposing Rahul Gandhi’s campaign of caste census and removal of the 50 percent reservation cap validated by the Supreme Court.

The BJP right, from the 2014 elections, started mobilising the Other Backward Classes in a clever way to garner votes.

Since the RSS/ BJP accepted caste mobilisation from then, as they brought in Modi, an OBC from Gujarat, as the prime ministerial candidate, they started playing the caste game very cleverly like in a chess.

Caste connections

In states where the Shudra upper layer community like Yadavs in Uttar Pradesh were rulers for some time, they mobilised the lower OBCs dissatisfied with the ruling caste leadership. They managed to win a majority of MP seats and power in that state twice.

In Telangana, where the Reddys and Velamas who happen to be the Shudra are ruling castes, in the 2024 election the BUP focused on Kapus and Mudirajus, with a slogan Easari BC mukhya mantri (Now, a BC chief minister).

It is known that the Reddys are with the Congress and the Velamas are with the BRS in Telangana. Among the Dalits, since the Malas are with the Congress, they specifically focused on Madigas.

Just before the 2024 general elections, to garner Madiga votes, Modi himself addressed a special Madiga public meeting.

Sub-caste factors

It was at this meeting that he promised to help the Madigas to overcome the legal hurdle in the Supreme Court. Hence, the Union government proposed before a Supreme Court seven-judge bench that sub-caste demands for divisions in reservation was not unconstitutional.

Finally, the court upheld the sub-caste categorisation for reservation as constitutionally valid.

The RSS/BJP forces do not think that all such divisive politics are dangerous. They project their caste-based divisions as nationalist.

Also read | ‘Dalits among Dalits’: Why TN introduced internal reservation for an SC subcommunity

But to implement that judgment, per the Supreme Court ruling, objective and verifiable data about each sub-caste across India is a must. This sub-caste reservation judgement is applicable to all sub-castes that ask for justifiable share in the reservation pool – SC/ST/OBCs.

Hence, the implementation of the Supreme Court judgment is not possible without

having national caste census data collected by a constitutional body – the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

Caste census against unity?

The Modi government does not want to collect caste data in the forthcoming national census. Now, both the Supreme Court judgment and the Modi government have created a new headache for state governments as several sub-castes are asking for the implementation of the SC ruling and the Centre is not willing to collect credible caste data.

It is in this context they have started the campaign that a caste census will divide Indian society.

As the Congress, particularly Rahul Gandhi, is campaigning about the caste census as an X-ray of the society’s socio-economic profile, the upper castes, particularly Brahmins, Banias, Ksatriyas, Kayasthas and Khatris, are opposing caste details.

The RSS/BJP’s interests are enmeshed with these five castes, more so in North India.

New slogan, new tactic

In order to overcome this problem, the BJP has started a campaign ‘Ek rahenge toh safe rahenge. Of course, since the 2024

elections, Modi and Amit Shah have started a drive to retain the OBC vote share by saying that if the Congress takes power, OBC reservations will be reduced and Muslim reservation will be increased.

Now, they have started openly saying if the Congress comes to power, everything will be given to Muslims. They are openly saying that SC/ST/OBCs will lose every benefit if the Congress comes to power in Maharashtra.

Also read | The tedious lightness of quota reform

They want to draw a clear line between Indian Muslims and the rest of the population because the Muslims are aligned

to the Congress for quite a long time in terms of vote.

The Muslim viewpoint

The Indian Muslim community for a long time did not accept reservation ideology as they went on denying the existence of caste among them.

But over a period, they too realised that caste and poverty and educational backwardness among them are interrelated.

It was the Congress-headed UPA government that constituted the Sachar Committee. Once that report was out, the Muslims realised that their educational backwardness is a serious problem. Their

backwardness is also related to their communal cocoon.

The RSS and Muslim conservatives competed for religious conservative politics.

In the process, national development suffered. Now it has become a competitive contest for reservations. The Muslims are willing to accept caste census as well.

The Muslim divide

The Shudra upper castes which thought that using reservation was below their social status now want to get into the reservation system. The ideology of reservations has become the central issue in national politics.

Hence castes like Reddys and Marathas are not averse to caste census.

The socioeconomic census that includes caste census will bring out the real status of each caste including that of the castes that exist among Indian Muslims.

There are upper castes among Muslims who benefitted from Mughal and post-Mughal feudalism and conservative Islamism. For example, the poor lower caste Muslims were pushed into backward Madarsa Urdu medium education whereas the rich upper caste Muslims got English medium education from pre-Independence days. This cordon among Muslims also must be broken.

Caste census is needed

national demand for caste census and fare distribution of welfare schemes and also reservation benefits in education and employment.

Only a caste census and expanding the welfare net to the most deserving will expand the Indian middle class that would sustain the modern developmental process.

(The Federal seeks to present views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. The information, ideas or opinions in the article are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Federal.)

Kancha laiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist and author. His latest book is The Clash of Cultures – Hindutva – Mullah Conflicting Ethics.

-

ANTI-FREEDOM EXPRESSION OF LEFT-LIBERALISM HAS REACHED A FRENZIED PHASE: I CONDEMN AND GIVE A CALL TO STOP IT.

ANTI-FREEDOM EXPRESSION OF LEFT-LIBERALISM HAS REACHED A FRENZIED PHASE: I CONDEMN AND GIVE A CALL TO STOP IT.

PRESS STATEMENT

On 2 October, 2024 I was scheduled to speak in the Malayalam Manorama Arts and Literature Festival at Kozhikode held from 1to 3rd November. The organizers under the directorship of a retired IAS officer, NS Madhavan, disinvited me on the pretext of possible protests against my article in Sakshi, a Telugu newspaper with the title, The only Way out to ISRAEL-PALESTINE IS TWO NATION FORMULA . After my air ticket was booked, they called and informed me that my presence could provoke protests and possible violence. Neither the CPM Government, nor the Malayalam Manorama group of Kerala realized that opinions on national and international issues should not be allowed to result in threats and cancellation of invitations to speakers; this has potential to destabilize Indian democracy itself.

The second dis-invitation for a Library opening programme by a Marxist-Leninist group called the Rajanna group to be held on 11 November, 2024 at Vemulawada is more shocking. The group’s popular singer Vimalakka called me on 31 October, and asked me to be the chief guest of a library building opening programme built in memory of Rangavalli, who was brutally killed by the police 25 years ago. At that time, I was a civil rights activist and knew her in her early activism days. Though normally I do not associate with Maoist-Naxalite group meetings, even as a speaker, I accepted this invitation because Rangavalli was a woman leader and opening a library in her memory was a positive development, that too in a rural area.

Quite shockingly, after three days a Whatsapp message comes from Vimalakka that there are serious objections to ‘your Sakshi article on the Israel-Palestine issue; you must re-think’. I replied that I have my position. It was for them to agree or disagree. This invitation too followed a similar dis-invitation.

One is a major newspaper in Kerala and the other is a Marxist-Leninist party. Both disrespected my freedom of expression and self-respect.

Left liberals joining hands with fundamentalist Muslim youth have become the stick on social media to attack my right to freedom of expression. Actually, they are only pushing the Muslims of India into a deeper crisis in the world order led by Trump, Modi and Netanyahu. They also seem to be bent on instigating youth to disrupt the liberal atmosphere in Telangana, available because of Congress rule.

Leftists think that the Jews should be thrown out of Israel; only Palestinians have a right over that land. Leave alone Ambedkar who supported the settlement of Jews in Israel in 1948, they have not read what Lenin and Marx said on the Jewish question.

It is up to them to live in their blissful ignorance, but they have no right to insult me and abuse my right to freedom of expression and self-respect.

I am open for a debate on my stand on this issue in any public forum.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

Hyderabad, 9 November, 2024.

Prof. Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

Former Director, Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy,

Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Gachibowli, Hyderabad-32

Ph.No.- 040 23008335 Mob- 9704444692

http://www.kanchailaiah.com